By Debra Lawless

(This article appeared in slightly different form in The Journal of the Cape Cod Genealogical Society, Spring 2013.)

This is the story of the remarkable three-decade collaboration of William Emery Nickerson, who founded the Nickerson Family Association in Chatham, and Anna Chandler Kingsbury, his genealogist.

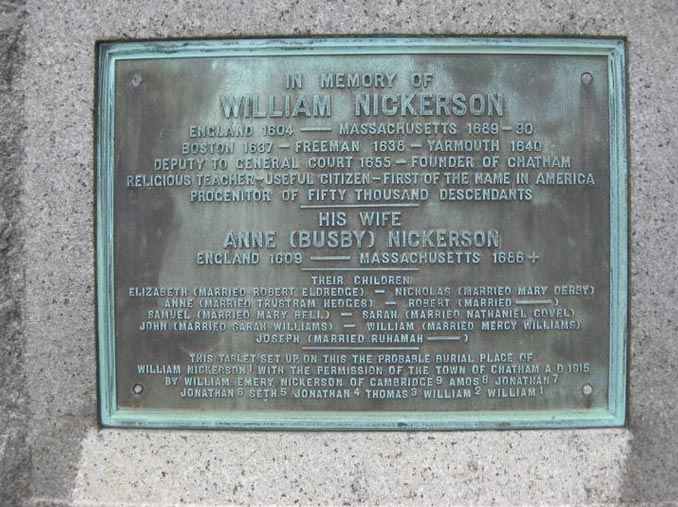

In June 1897 Nickerson organized a reunion of those descended from William and Anne Busby Nickerson. That couple had traveled from England in 1637 with four children—six more would be born in America—and after living in Salem, Boston and Yarmouth, bought the land that is now the Town of Chatham. Over five hundred Nickersons attended the reunion on a Saturday in June near William’s old homestead in Chatham.

“Just one fault,” joked Bertha Nickerson a week after the event. “There was so much sand all the way.”

Nickerson descendants proved enthusiastic about the genealogy forms Nickerson mailed out asking for family information to compile a genealogy of the Nickerson family. Nickerson also asked that Nickersons expend one dollar for membership in the new lineage society to help pay for an “amanuensis” to compile the forms. As the forms poured in to Nickerson’s office on Pearl Street in Boston, the task ahead appeared daunting. “A large portion of the genealogical blanks which come in are very poorly written, and in a great many of them no attention whatever has been paid to the order of arrangement given in the blank,” he wrote. By 1899 Nickerson had received the names of between ten- and fifteen-thousand living and dead kinsmen which he planned to use to create “the total family list as far as it can be obtained.”

Nickerson, born in Provincetown in 1853, was on his father’s side a ninth generation descendant of William Nickerson, and on his mother’s side traced his line back through Pvt. Solomon Covel of Eastham who fought in the American Revolution. He graduated from MIT in 1876 with a degree in chemistry and for years worked perfecting inventions in various fields such as leather tanning, gold assaying, elevator safety and incandescent light bulbs. In 1901 he turned his skills to improving the new Gillette safety razor by creating a sharpening machine. Although it is frequently remarked that Nickerson did not have a head for business, he amassed a fortune through his work with King Gillette. He served as a trustee of Boston University and donated to the school under the name “the mysterious Mr. Smith.” The university’s Nickerson Field is named for him.

When Nickerson’s clerk Miss MacKinnon “was taken sick” in April 1899, Nickerson brought in Kingsbury as “temporary help.” From the tone of a note Kingsbury wrote to the ailing MacKinnon that June, asking MacKinnon to send back the key to the office desk and signed “Affectionately yours, K.” we might deduce that Kingsbury was acquainted with MacKinnon, who may well have recommended her for the position.

In June, Nickerson, who lived in Cambridge, wrote to Mary Louise Nickerson of Chatham that Kingsbury “is, I am happy to say, very efficient and satisfactory, and much interested already in the work.” Yet seventy years after her death, the figure of Anna Kingsbury, despite her decades of groundbreaking work, remains a shadowy one.

Kingsbury descended from Joseph Kingsbury (also spelled Kingsberry) who settled in Dedham in 1637. Born on 12 May 1870 to Lyman Edward and Louisa Hewlett Holland Kingsbury, she was raised in Needham. At the time of her birth her father worked as a brick mason. Kingsbury was a late baby with an elder brother, George Lyman Kingsbury, seventeen years her senior—the same age as Nickerson– already working at a farm. By 1880 both Lyman and George listed their occupations as “provision dealer” with the word “butcher” crossed out. The family was then living on Webster Street in Needham, and had taken in Kingsbury’s cousin Anna P. Chandler, six, and Eliza Holland, forty-nine, Kingsbury’s unmarried aunt. The household also had a servant, Hanna J. Fitzgerald, sixteen.

Kingsbury was educated in the Needham public school system, and graduated from high school there. She taught school from 1890 to 1895, and then studied stenography and bookkeeping at the now-defunct Comer”s Commercial College at 666 Washington Street in Boston. “Comer’s pupils receive actual practice in business from beginning to end of course by teachers who are specialists,” boasted an 1895 ad for the college. Most Comer’s graduates headed into employment as office workers, and it was no doubt with the goal of hiring office help that Nickerson brought Kingsbury into his office. Although Kingsbury would have become proficient in stenography and typing while at the school, she was most likely not trained in genealogy.

Still living at home in Needham, Kingsbury commuted in to the office at 12 Pearl Street, Boston that Nickerson established for his genealogical work. (Nickerson had a separate office at Gillette Safety Razor Co. in South Boston.) While Nickerson had been paying his “amanuensis” MacKinnon at the rate of ten dollars per week, he started Kingsbury at the rate of seven dollars per week on 24 April 24 1899. Kingsbury’s first task was to re-copy and file the genealogical forms sent in by Nickersons so that an alphabetical list could be begun. As early as 1903 Kingsbury lists her occupation in the Boston City Directory as “genealogist,” not clerk.

Lyman Kingsbury, Anna’s father, had died in 1890, and Kingsbury juggled running the household in Needham with working in Boston. It was a challenging task, and in February 1907 Nickerson told a correspondent that Kingsbury was taking time away “for her health.”

“I was very much tired out and the change did me good,” Kingsbury recalled three years later. From November to March she visited Florida, camping for a part of the time in the woods of Central Florida. “We slept in tents, had a canoe in the prettiest lake, a mile in diameter, and so used to go out and catch our fish for breakfast or dinner, starting just about sunrise,” she wrote.

For five-and-a-half years a “Miss Fox” with a “charming personality” assisted Kingsbury, and the pair traveled together to interview Nickersons on Cape Cod and in other parts of Massachusetts. At that time Kingsbury sometimes came into the office only on Tuesdays and Fridays, due to her “home duties,” as Miss Fox could be trusted to greet any visitors. But Miss Fox quit to marry in July 1909, leaving Kingsbury alone in the Pearl Street office much of the time.

The genealogy, like any monumental undertaking not completed in a year or even a decade, discouraged Kingsbury at times. “It does progress, but I feel sometimes as though it was a mountain upon our hands,” Kingsbury wrote in 1910.

When Kingsbury turned forty in May 1910, she was still living with her increasingly invalided mother Louisa, seventy-six, and Louisa’s elder sister Eliza Holland. Kingsbury’s brother George lived next door with this wife Alice, forty-five, and two young daughters. George was now the town assessor. Kingsbury again lists her profession as genealogist on the census form.

This was a bittersweet period in Kingsbury’s life. In December 1911 Aunt Eliza, eighty-one, died at the family home in Needham. “My mother, although realizing it at times, forgets it for long, a blessing, perhaps, weak and feeble as she, herself, is,” Kingsbury wrote to Nickerson on 15 December. And then early in 1913 Louisa herself died. She was Kingsbury’s “precious care for the past three years always at night and partially by day,” and Kingsbury felt the “loss of the care” keenly. “It seems most strange and unreal.” Three months later, Kingsbury wrote to Chatham historian William C. Smith that she looked forward to a vacation on the coast of Maine for a few weeks in August after the “strain” cause by the illnesses and deaths of her mother and aunt. That summer she also checked into the family-style hotel the Hawes House on Water Street in Chatham and used that as her base while she looked up records at the Barnstable County Courthouse.

In the fall of 1913 Nickerson, who had already expended over fifteen-thousand dollars on the genealogical work, felt other Nickersons should share in its expense. By then Kingsbury had collected the names of more than thirty-thousand descendants of William Nickerson. Kingsbury wrote letters to potential Nickerson family patrons looking for an additional three-thousand dollars to keep the project afloat, but after letters, calls and visits, the pair managed to drum up pledges for only twelve-hundred dollars. “The result was discouraging and at last I decided to abandon all active work upon the Nickerson Genealogy for a time until such time as members of the family were sufficiently interested… or I was in a better situation to continue it,” Nickerson wrote.

When Nickerson put the genealogy on hold, he and Kingsbury took up other genealogical projects. “This will occupy me part of the time and I am going to see what else I can do to fill the other time,” Kingsbury wrote to the former Miss Fox, now Mrs. Elmer Jacobs, on 19 November 1913. She said she regretted that she and Jacobs no longer worked together. “How I should have liked it, both the having your companionship and knowing that the work was moving steadily along.” Kingsbury signs the letter “lovingly, your friend,” and adds, “please let me see or hear from you occasionally, as you can.”

In April 1914 Nickerson appended a note to a letter to a well-to-do Nickerson in Chicago saying that “my assistant Miss A.C. Kingsbury would be pleased to do some outside work besides the work given to my various lines other than Nickerson. Should you know of anyone desiring genealogical work done, I wish you would mention her.” Kingsbury was still operating from 12 Pearl Street in 1915 when she published her first “Note” in TheNew England Historical and Genealogical Register. Her topic: Joseph Collins Sr. of Eastham who married in 1671. She would eventually publish three notes in the Register between 1915 and 1933 and two of her monographs would be listed under “Recent Books.” As a testament to the influence of Kingsbury’s research, her typescript “Vickery Family in Notes and Compilations, Genealogical Lines of William Emery Nickerson” would be quoted in a Register article on seventeenth century Hull in 1989.

At some point after the deaths of her mother and aunt, Kingsbury closed up the family home and moved in with her brother George. By 1940, Kingsbury would at last own her own home at 805 South Street, Boston.

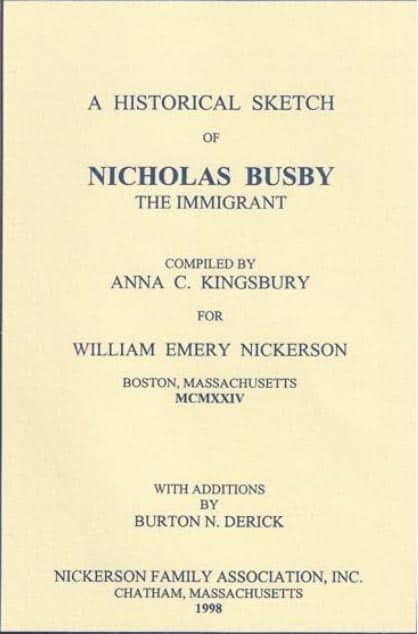

Kingsbury’s relationship with Nickerson was in some ways a peculiar one. While in April 1914 Nickerson refers to Kingsbury as “my assistant,” in an August 1914 letter he refers to her as “my clerk,” and certainly she did fulfill many of the duties of a clerk or a secretary. Yet she continuously called herself a genealogist, and in 1920 she lists her occupation on the census as “genealogist” employed by a “genealogical society.” One wonders if either Kingsbury’s gender or her relative lack of affluence, compared to Nickerson, prevented Nickerson from referring to her as a colleague, a genealogist, or an author. Between 1923 and 1925 Kingsbury published four monographs on seventeenth century Americans, the titles of which all begin with the words “A Historical Sketch of.” The privately-printed books’ copyright pages list the author as “Anna C. Kingsbury for William E. Nickerson,” suggesting a patronage relationship perhaps unusual in the 1920s. When Kingsbury wrote a letter for Nickerson she signed it “per K.” under Nickerson’s typed name.

When Nickerson died in 1930, the nascent Nickerson Family Association, which he had founded in 1897, went dormant. When the group re-formed, in 1956, it took off, and today, with over one-thousand members, it is one of the rare family associations owning real estate. In 2012, NFA members published the fifth volume of the genealogy tracing William and Anne’s descendants. An additional volume is in the works.

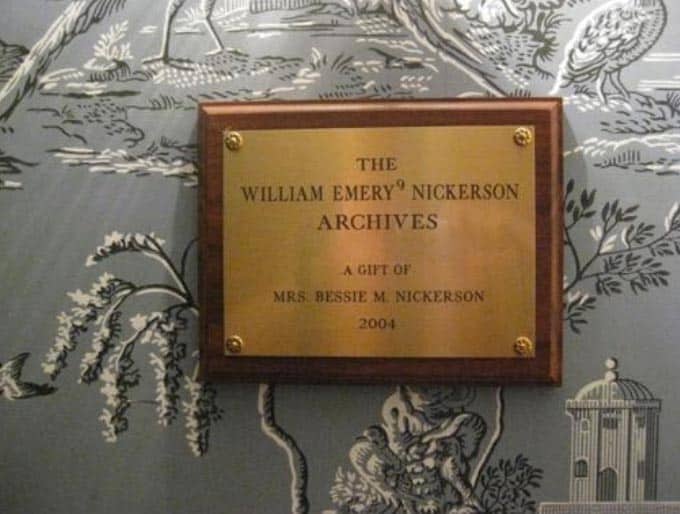

Kingsbury’s association with the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) began in 1902, when she was elected a member. In 1942 she gave the fruits of her forty years of genealogical research to the society. Again, the patronage relationship comes through: “It is gratifying to know that we have in our possession the William E. Nickerson Genealogical Collection. This came to us from the estate of William E. Nickerson of Boston, the work of Miss Anna. C. Kingsbury, who for many years was engaged by him to do this work.”

Kingsbury became a “life member” of NEHGS on 24 June 1941. On 16 November 1943 she died, in her hometown of Needham. The memorial in the Register credits her with “arranging and compiling” material for the Nickerson family genealogy “which she completed and gave” to the NEHGS library.